Recap Digest: Mad Men 7.14, "Person to Person"

Having worked as David Chase’s right-hand man on the last couple of seasons of The Sopranos, it makes sense that Matthew Weiner would end Mad Men with an echo of that series' famous cut to black. Cutting to the famous “I’d Like To Buy The World A Coke” ad, strongly suggesting (but not stating outright) that Don Draper returns to New York with a fresh idea, a new outlook on himself, and a new commitment to his children made for a slightly elliptical, mostly satisfying end to the show.

For a minute there it seemed like Don was going to reject advertising once and for all and go back to his roots tinkering with cars, and absent the fact that he has children, I would have been happy with that end to the character’s journey—at least he’d be himself.

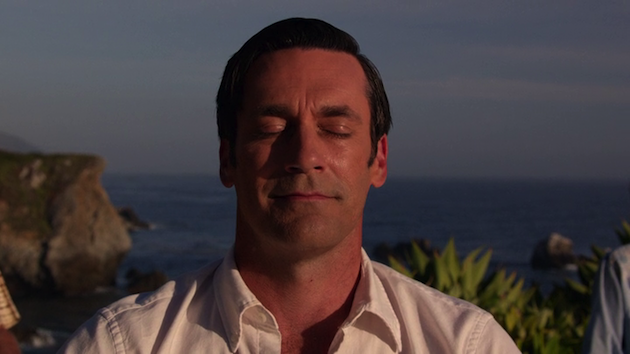

Sending him to a spiritual retreat in Big Sur was not something I saw coming at all, but Don did come to some personal revelations there, particularly in realizing during another man’s speech in group therapy that his feelings of isolation are not unique, that he is loved. And though he relents when Betty insists that Gene and Bobby go to live with her brother after her death, the show strongly suggests a change of heart on that front, when one of the other enlightenment-seekers talks about being abandoned by her parents and spending the rest of her life watching the door for them to come back. That seemed to strongly resonate with Don—how could it not? It’s the way he feels himself!—and paired with his Big Idea on the mountaintop, it looks like Don Draper is going to be just fine.

Even if Don didn’t come back, the show gives us a thoughtful, articulate Sally, stepping up to help raise her younger brothers and talking all kinds of sense, insisting that the boys should stay with Henry. That may or may not play out the way she wants it to, but she’s clearly going to be fine.

There were a couple of odd notes in this finale for me: I didn’t quite understand the point of the encounter with the woman who almost stole Don’s cash and wedding ring, and I felt like Stan and Peggy’s sudden realization that they’re soulmates was more than a little rushed. I liked Joan’s starting her own production company, and I loved that this show slipped a cocaine scene in right before the end to properly usher in the ‘70s.

And of course ending on that Coke ad was appropriate. In real life this ad began running in 1971. I was born in 1973 but I distinctly remember this commercial, which means that it must have run for seven or eight years at least, which is crazy staying power for an ad campaign, and the perfect capper for Don Draper’s career.

Vulture’s Matt Zoller Seitz, whose Mad Men recaps have really been an indispensable companion to the show, distills the finale to two key scenes:

One of the most discussed episodes of The Sopranos’ final season was “Kennedy and Heidi,“ in which Tony Soprano went on a dreamlike trip to Las Vegas, took peyote and stood on a hilltop shouting “I get it!” He didn’t get anything. But I think Don, who ends “Person to Person” on a hilltop looking inward just like Tony, does get it. What does he get? A (possible) answer can be found in two other scenes at the retreat. One is Don’s phone call to Peggy, which sounds very much like an addict making amends for past misdeeds in the early stages of recovery. ("Person to person” is how Don calls Peggy and Betty long-distance.) The other is the refrigerator monologue by a fellow retreat member, Leonard (Evan Arnold: remember his name). It’s about feeling unloved and invisible, so much so that you retreat within yourself and fail to recognize that, in their awkward and often messed-up way, people are trying to reach out to you, and “you don’t even know what that is.” Don’s moment of clarity, such as it is, occurs here. He stands up from his chair in a medium shot, and over his shoulder we see a painting of an opened flower; slightly abstracted, it suggests a sunburst. Then he embraces Arnold, as a young child might embrace a family member in distress: reflexively and without any ulterior motive. Don has nothing to gain from doing such a thing. Don is a man who, throughout the show’s run, treated the expression of emotion as a sign of weakness, unless he was so bereft (or drunk; the two were usually connected) that he couldn’t control himself in that way any longer. Think of how many times Don responded to other characters’ tears with “Stop” or “Get a hold of yourself,” and then practically ordered them to drink. But maybe it’s not Don who’s embracing a stranger. It’s Don plus Dick Whitman, a name Don has used in the last few episodes, with surprising ease. Maybe what we’re seeing here is the reconciliation of Don Draper and Dick Whitman.

Calling the episode “damn near perfect,” The Hollywood Reporter’s Tim Goodman praises the open-endedness of the ending:

Weiner — who appropriately wrote and directed the finale himself — managed a couple of storytelling styles with aplomb. First, he not only wrapped up most of the main characters’ stories, but he did so in an almost unfailingly upbeat manner (save Betty’s more downcast end) — without making any of those happy endings seems saccharine or unbelievable (nor was Betty’s too maudlin). Weiner simultaneously presented the “end” as open-ended, which could have easily been canceled out by the appearance of wrapping up those very stories. By that I mean that on one level the stories the Mad Men characters live go on, even though we have resolution and closure on another level. I thought that’s how Weiner would end it, but of course had no idea how open he’d leave it. As an example, we are left to assume (correctly), that Don goes back to New York, back to McCann-Erickson, and regains his old job and the Coca-Cola account, plus delivers a TV ad for the ages. We don’t see that happen, but we know it does. Which allows viewers to continue his story in their minds, fueled not only by what Weiner gave us (Don’s existential evolution and recognition of the failure of his bad habits), but also whatever else they might conjure up. For example, we can easily imagine that Don does see Betty and will be there in some form when she dies. And that it’s possible Don won’t abide by her wishes that the kids go to her brother – that Don will step up and be more in their lives. This is what closing a window (for the viewers) on lives that still go on (for the characters) allows. We can imagine whatever ending we want, based not only on the facts and hints presented by Weiner in this episode, but also in previous episodes. And at the same time we are all free to imagine the future we’re not seeing every Sunday – that Peggy and Stan will continue to be in love and maybe get married. That Pete and Trudy are happy in Wichita. That Roger and Marie’s marriage is a happy one that lasts. And that Joan’s company thrives. If you’re constructing how exactly to make not only a believable and well-told finale, but one that will satisfy both fans and critics while leaving more to the imagination for those who want to think about how the Mad Men story goes on, well, there it was.

HitFix’s Alan Sepinwall is disappointed:

This is a show whose opening credits — depicting an ad man who has his whole world stripped away, sending him plunging to the ground, only to end up back where he started, lounging confidently, a cigarette dangling from his hand — promised this exact journey, and whose stories time and again dealt with the tremendous difficulty of personal change. Don, Joan, Roger, Peggy and Pete weren’t Baby Boomers, who would get to find themselves as Camelot gave way to Woodstock; they were adults at the start of this tumultuous decade, and though all grew and changed in different ways, the change often came at deep personal cost, and not all of it stuck. Time and again, we saw Don vow to stop cheating, to stop treating Peggy like garbage, to be more involved in his children’s lives, and we saw him stick to those vows… for a little while. And then he went back to doing what was easy. This latest journey seemed like it was going to be different. He spoke of advertising in the past tense (in the finale, he tells Anna’s niece Stephanie that he’s retired), got absolved of his role in Donald Draper’s death and gave a would-be Dick Whitman a chance to avoid committing the same kind of original sin, and seemed to be heading towards something new. There was hope there for a new, better version of Don — one that would last past the first stumble, or the first bit of temptation. Instead, we didn’t get a new Don. We got a new Coke ad(***). He didn’t become a better human; just a better ad man. Which was the only thing he was consistently good at to begin with. So, no, ending on the Coke jingle didn’t fill me with uplift and contentment, particularly after a finale that took both Don and the show so far out of their comfort zones in bringing him to that New Age retreat along the California coast, in a way that seemed to promise something deeper than he ultimately proved capable of becoming. But perhaps that was the point: that even a journey of thousands of miles — involving heartache and personal injury and devastating news from the homefront — and even a visit to a place this peaceful and open and lacking in guile or commerce wouldn’t be enough to fundamentally alter who Don is at his core and what matters to him. And if that’s the ending Weiner was shooting for (which, again, we have to make our own interpretation on), then that’s ultimately true to the nature of the show and the man, even as it’s disappointing to have him turn out that way, and even as parts of “Person to Person” dragged mightily in getting us to the two different groups of people on a cliff.

Grantland’s Andy Greenwald is more concise:

MAD MEN is one of my favorite shows of all time. I loved it this morning, I love it now. But I thought that finale was unambiguously awful.

— Andy Greenwald (@andygreenwald) May 18, 2015The A.V. Club’s John Teti unpacks Don’s time at the retreat:

“You can put this behind you. It will get easier as you move forward.” Peggy Olson once heard a similar forecast from Don when she abandoned her own newborn son. Peggy took him at his word. Not Stephanie. “No, Dick, I don’t think you’re right about that,” she says. Don has put past lives behind him. He kept moving forward. And how much easier has it gotten for him? Don ought to see their common plight, but he doesn’t. That’s just another instance of Don failing to connect, person to person, with those around him. In an exercise where he simply has to turn to a fellow human and express how he feels about them, Don looks around the room in consternation. The woman who’s partnered with Don in the exercise finally reacts out of frustration, pushing him away, which deepens his confusion—an archetype for so many of his failed relationships. Then a man named Leonard puts the archetype into words. There’s a lot of talk about the fearsome power of “shoulds” in the seminars at this retreat, and Don spends much of the episode trying to do the things he believes he should do—go home to his kids, for instance, or take care of Stephanie. But Leonard speaks to a deeper “should,” the one that says we should love and be loved. “You spend your whole life thinking you’re not getting it, people aren’t giving it to you. Then you realize: They’re trying, and you don’t even know what it is.” The monologue has Don’s rapt attention as he hears from a kindred spirit—someone else who’s isolated not by their failure to give love but by their inability to receive it. Don is the opposite of Leonard in some ways. Leonard laments how uninteresting he is, while Don is used to being the center of attention when he walks into a room. But their fundamental pain is the same. Leonard describes a dream of being on a refrigerator shelf. He’s aware that there’s a party going on outside, a joy that he can see in the smiles of people who open the door and look in on him. But they never pick him to join the party. Leonard’s vision is a permutation of Don’s purgatory, in which Don is surrounded by tantalizing images of a happy, fulfilled life and maddened by the impossibility of making them real. Like Leonard, Don can describe the happiness that he envisions—in fact, he’s built a career out of describing it—he just can’t sample it for himself. Don faltered in that first exercise, when he was asked to wordlessly show his feelings toward another person in the room, but now he can’t hold himself back. He wraps his arms around Leonard and sobs, an unspoken show of gratitude for someone who shares his fundamental struggle to connect.

Todd VanDerWerff at Vox picks up that thread:

Imagine, for a moment, a whole show about Leonard, the man whom Don comforts, a show where Leonard drifts through a whole decade feeling like he is ignored, unnoticed, slowly coming apart. That is, in some ways, the story of Don, but this is not a man who possesses Don’s glamour and suave handsomeness. He is, instead, just some guy, out on the edges of life, waiting for things to make sense. The genius of Mad Men is in how it suggests that everybody is that way, no matter how much they seem like they have it together. Don Draper’s central flaw — that he constructs a Don Draper suit that he thinks covers up his bruised, aching Dick Whitman self — is the flaw all of us share. We all suspect people can see our worst selves, that they might push us away if they found out who we really are. There are millions of stories just like this, behind the locked doors of houses we pass on late-night walks, sitting in the cars we find ourselves idling beside on the freeway. This is a big planet and a big country, filled with so many people and so many stories, but, really, one story — that of searching, endlessly, for someone who will see us and understand us and know us and not look away.

And fashion bloggers Tom and Lorenzo, whose “Mad Style” fashion recaps have consistently been one of the great gifts to the recap world, see the ending as having one of two meanings, open to interpretation:

So which one’s it gonna be, hotshot? Hope or cynicism? Note that both interpretations end roughly at the same conclusion: Life goes on, which can be taken either as a hopeful sentiment or an ironically fatalistic one. How very appropriate of Weiner to end the show this way and on these questions. Of course we’re writing this in the middle of the night, hours after the episode aired. For all we know, by noon tomorrow, Weiner will be giving interviews to the New York Times giving the definitive answer to the question. At the very least, it comes across intentionally vague. Then again, we were surprised Weiner ended the show by implying that the fictional Don Draper might actually be responsible for the rightly praised work of the very real Bill Backer, considering he’s said more than once that he had no intention of taking credit away from the real work of real people. All bets are off, apparently. But without coming right out and saying so, the episode was constructed in such a way as to make you seriously consider that Don was taking inspiration from his own experiences to come up with the legendary ad; from Peggy pleading with him to come home (“I’d like to buy the world a home”) to Leonard’s feeling that his family didn’t love him (“and furnish it with love”), to the ethnically diverse grouping of hippies on a hilltop with him at the end, and even to some sly costuming winks. We’re inclined to believe that Don didn’t really achieve any form of true enlightenment. He had another breakdown, ran away, hit rock bottom again, and then used that to come up with a killer ad. It’s what he’s always done. And the idea that he did it again here, even as he was facing the destruction of his own family, and did it better than he’s ever done it before, tells us that Don Draper will never truly change. That wasn’t enlightenment at the end; it was capitalism, grinding ever on. Now, it’s possible that Don cynically turned his experiences into the Coke ad while at the same time reuniting with his children under one roof and learning to accept love in his life, but that seems extremely unlikely given that utterly heartbreaking conversation with Betty, where they both come face to face with the truth of how limited a man Don Draper is. “I want to keep things as normal as possible, and you not being here is part of that.” It could have come across like a bit of a bitchslap, but it really was just the wearying truth of the matter. From Betty’s perspective, Don couldn’t possibly be counted on to be a father to his children. And while we think a lot of how this series ended could be open to interpretation, we simply cannot fathom an ending that has Don enlightened, unburdened of the past, a loving father to his children AND at the very top of his game in the advertising world. That’s just not how Matthew Weiner sees things, nor would such an ending be true to the show.”What did you ever do that was so bad?” Peggy asks him. “I broke all my vows, I scandalized my child, I took another man’s name and made nothing of it,” Don replies succinctly. “That’s not true,” Peggy offers weakly, but it is. All of it is. No, as we see it, either Don gave up everything – including his children – in order to find some sort of peace or he went right back to the remains of his old life largely unchanged and wrote the best ad of his career. We are inclined to think it’s the latter, but we’ll enjoy hearing other people’s interpretations of the former.