Recap Digest: Better Call Saul 1.8, "RICO"

As the shockingly great first season of Better Call Saul moves into its homestretch, it’s becoming clear how the show plans to change its protagonist from put-upon do-gooder to scheming criminal lawyer (emphasis on ‘criminal’): by demonstrating the old saw that underneath every cynic is a disappointed optimist.

I can’t say I expected Jimmy’s foray into elder law to yield anything more important than a few Matlock jokes, but this show is surprising me yet again by turning it into a potential bonanza: his keen eye for scams (as a scammer himself) notices a pattern of overbilling at Sandpiper, the assisted-living facility he’s been trolling for clients, and next thing you know he’s looking at a potential multimillion-dollar class action suit for fraud.

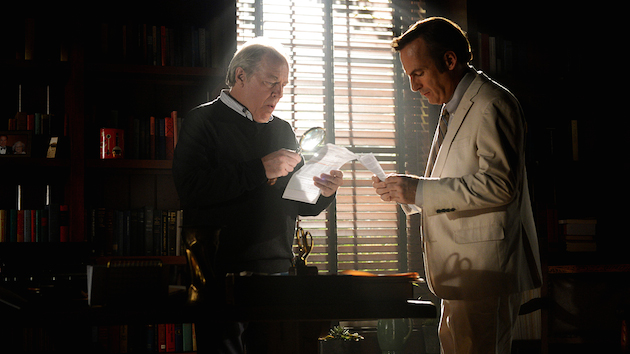

This is exciting stuff, exciting enough to draw Chuck out of his “retirement” and lend his reputation and gravitas to a meeting with opposing counsel that quickly reveals that they’re really onto something. But the seeds are already planted for how Jimmy’s going to be disappointed yet again: asking Kim to pull up relevant case files and print them at the HHM offices, using Chuck’s copier code, suggests that Hamlin is eventually going to get wind of the whole thing and muscle Chuck into bringing the case under HHM’s roof, leaving Jimmy once again out in the cold.

Seems like it could cause a pretty big rift between brothers. Big enough to make you want to change your name, maybe.

None of this would be so clear if we didn’t know where Jimmy will end up, but HitFix’s Alan Sepinwall is warming to the prequel format:

On the one hand, “Better Call Saul” would seem to be hamstrung by what we know is coming for Jimmy and Mike. Every time Jimmy seems close to some huge financial score, for instance, we know it probably has to fall apart somehow, because a Jimmy McGill who is a successful civil attorney has no need to become Saul Goodman. So when Chuck made the $20 million demand of the Sandpiper attorneys, my mind immediately began wondering how they would blow the case, and/or how they might win without any significant money going to Jimmy. But the more I’ve watched this season, the more I’ve come to view that predestined quality as a feature, not a bug. We know where Jimmy and Mike will be six years into their future. The “what” isn’t the important part of “Better Call Saul.” The “why” is.

Donna Bowman of The A.V. Club focuses on how the people around Jimmy react to him, and those reactions have shaped Jimmy:

If there’s a signature reaction to Jimmy in “RICO,” it’s dubiousness. In the cold open, Kim tries to shoo him and his mail cart away before he even makes it in the door: “I’m really slammed, just tell me what you need.” You get the feeling he’s been pestering her, presuming on the relationship implied by that full-on-the-lips kiss she gives him after opening the letter from the bar association. Later she doubts that Jimmy’s request for printouts of precedents and case law could really mean that he’s on to something. After his incongruous pleasantries about the opera, Schweikart—Sandpiper’s cocky suspender-snapping lawyer—doesn’t give Jimmy’s cardboard-and-TP demand letter any credence; “This is a shakedown and we both know it,” he explains with annoying certainty. Chuck soft-pedals the significance of the Sandpiper financial statements Jimmy’s so excited about—partly because he can’t believe he missed it himself, but partly because he’s accustomed to throwing cold water on Jimmy’s enthusiasms. (“Even a stopped clock is right twice a day,” Jimmy comforts him self-deprecatingly.) And he shakes his head at the dumpster-diving stunt, sure that Jimmy must have trespassed or burgled or something. Everybody assumes that if Jimmy’s doing something, it can’t be worth doing.

Entertainment Weekly’s Kevin P. Sullivan singles out the copy-room scene that reveals Jimmy’s distaste for Howard Hamlin:

I want to call out the next scene for a second because it’s a perfect example of the creative team approaching a sequence in a way that almost no one else on TV does. Howard interrupts a small celebration in the mailroom and asks to speak with Jimmy alone. Closing the door behind them, the others leave, and—at least in terms of sound—so do we. Cutting out the dialogue from Howard and Jimmy’s conversation could (wrongly) be taken as an empty style choice, but think about what we’re really missing here. We know Howard, and we understand Jimmy’s reputation at this point. By muting the sound, the show is demonstrating that we know these guys well enough to fill in the blanks ourselves and be completely right. This, in essence, is an exchange we’ve already heard, and the scene acknowledges this. Jimmy, no matter how hard he tries, cannot improve his station, because the people in power won’t have it.

Over at IGN, Roth Cornet points out the parallel track Mike is on:

Meanwhile, this week gave us another glimpse at the inner life of Mike Ehrmantraut. Mike and Jimmy have always been on a collision course, but just how – and why - their criminal paths will converge is beginning to crystalize. When Mike’s daughter-in-law Stacey indicates that little Kaylee is in need, we can make an educated guess as to where things are headed. Jonathan Banks’ Mike brings such depth to this series and it’s fascinating to see his backstory unfold. I do have to wonder where Better Call Saul will go once Mike and Saul are firmly on their path of iniquity, though. Wherever that is, I’m willing to take the ride with them.

And David Segal worries about the show’s female characters over at The New York Times:

On the other side of the ledger, the writers appear to be flummoxed about what to do with Kim Wexler, the HH&M associate who is Jimmy’s frequent co-conspirator. As a character, she is strangely bland and indistinct. All we know is that she is deeply sane, conflicted about her job and fond of Jimmy. In other words, she is one-dimensional by the standards set by the oddballs and headcases in this show. The only other scoop of vanilla in the cast is Stacey, Mike’s daughter in law. She’s a stressed out saint of a lady, and that’s it. For quirky, singular females, “Better Call Saul” has thus far provided us only with Betsy Kettleman, whose outer gloss of suburban housewife masked the heart of a mobster. But she’s been the exception. So a final question to chew on: Do the writers of “Better Call Saul” have a hard time writing nuanced and multilayered women? Put another way, isn’t it time for Kim to get interesting?